by Susan Wiedel

During the afternoon of May 2, 2014, a group of eleven undergraduate students and their instructor met at Pittsburgh International Airport, luggage in tow and passports in hand. While no longer strangers, we had spent the majority of our time together in class, not in the “real world”–and what we were headed for was not just an academic experience. We said goodbye to our families, checked our sizeable suitcases, found our way to the correct terminal, and seated ourselves in the uncomfortable utilitarian chairs, anticipating our departure.

Four months earlier, the students met for the first time in room 300 of the Old Engineering Building. It was the first Tuesday of the Spring 2014 semester (although the temperature was anything but spring-like). Slowly, a group of eight girls and three boys meandered into the classroom. Some students knew each; others didn’t. None of us knew much about the instructor, Alana, a woman so petite that she could have been mistaken for an undergraduate.

We all peered at each other, both excitedly and apprehensively, thinking, “These are the people I will be traveling with to Bolivia.” Hopefully we’d get along.

After a semester of learning about Bolivia, its history, culture and politics; after researching and writing proposals for our on-site projects; after completing all of the paperwork and obtaining our travel itineraries, we were ready for our six weeks in Cochabamba, Bolivia.

Eventually it was time to board the plane. I sat in my assigned seat in between Alana and the window. Even though it was one of the more dangerous aspects of flying, takeoff always thrilled me. Without electronic devices to divert the passengers’ attention, we had no choice but to focus on the plane gathering speed, the wheels lifting off the ground, the wings angling for a turn. As the plane rose in altitude, Pittsburgh began to diminish; the Cathedral of Learning, the goliath of a building that is the epicenter of the University of Pittsburgh, looked like a miniature replica.

The plane rose above the clouds. Finally, I thought. It feels real now. Alana, my classmates, and I had been anticipating this day for months, the beginning of our trip to Cochabamba, Bolivia. If you had asked me a year before, I would not have known Cochabamba existed (I could place Bolivia and its capital La Paz on a map just because I was friends with a Bolivian exchange student in high school).

It was my first trip to Latin America, and my classmates and I got to live with host families for six weeks and do research of our own design–all on someone else’s dollar.

Just whose dollar, I did not know–and neither did the other 500 Pitt students who had participated in this same program since 1972.

“The program kept me here, because suddenly this huge urban university shrank for me and the world became a subset of people who are interested in area studies, international things, and Latin America.”

Dorolyn Smith, a linguist who received both her undergraduate and masters degrees from the University of Pittsburgh, sat in her office at the English Language Institute while she recounted her undergraduate experience with the Center for Latin American Studies (CLAS).

“I left Pitt with a really broad, good overview of Latin America as a region, with an appreciation with all those cultural characteristics that it had in common, but a recognition that there were still individual differences within countries, kind of like looking at a salad, and you see the whole salad but you can still see the individual elements in it, but together those elements contribute to a really good salad,” Smith explained. “That’s helped me a lot in teaching English to students from different countries of the same region.”

In 1973, Smith participated in the second Seminar/Field Trip offered by CLAS. After taking a class on the host country and the research process in the spring, Smith traveled to Guarne, Colombia where she spent six weeks living with a Colombian host family. The family lived on a farm twenty minutes outside of the town; when Smith walked down the road she would always pass the house of one man who did not approve of her presence there. He would yell at her, “Yankee spy, go home. Cuerpo de paz, Yankee spy, go home.” She always responded, “No soy cuerpo de paz ni soy Yankee spy.” He’d reply, “Yeah, yeah you are cuerpo de paz so you are Yankee spy.”

In 1973, Smith participated in the second Seminar/Field Trip offered by CLAS. After taking a class on the host country and the research process in the spring, Smith traveled to Guarne, Colombia where she spent six weeks living with a Colombian host family. The family lived on a farm twenty minutes outside of the town; when Smith walked down the road she would always pass the house of one man who did not approve of her presence there. He would yell at her, “Yankee spy, go home. Cuerpo de paz, Yankee spy, go home.” She always responded, “No soy cuerpo de paz ni soy Yankee spy.” He’d reply, “Yeah, yeah you are cuerpo de paz so you are Yankee spy.”

To Smith, people-to-people interactions opened her eyes to the power of preconceived stereotypes. “When you’ve got that kind of belief running around, and the belief is fairly common in Latin America, I think knowing individuals can only be good,” she said.

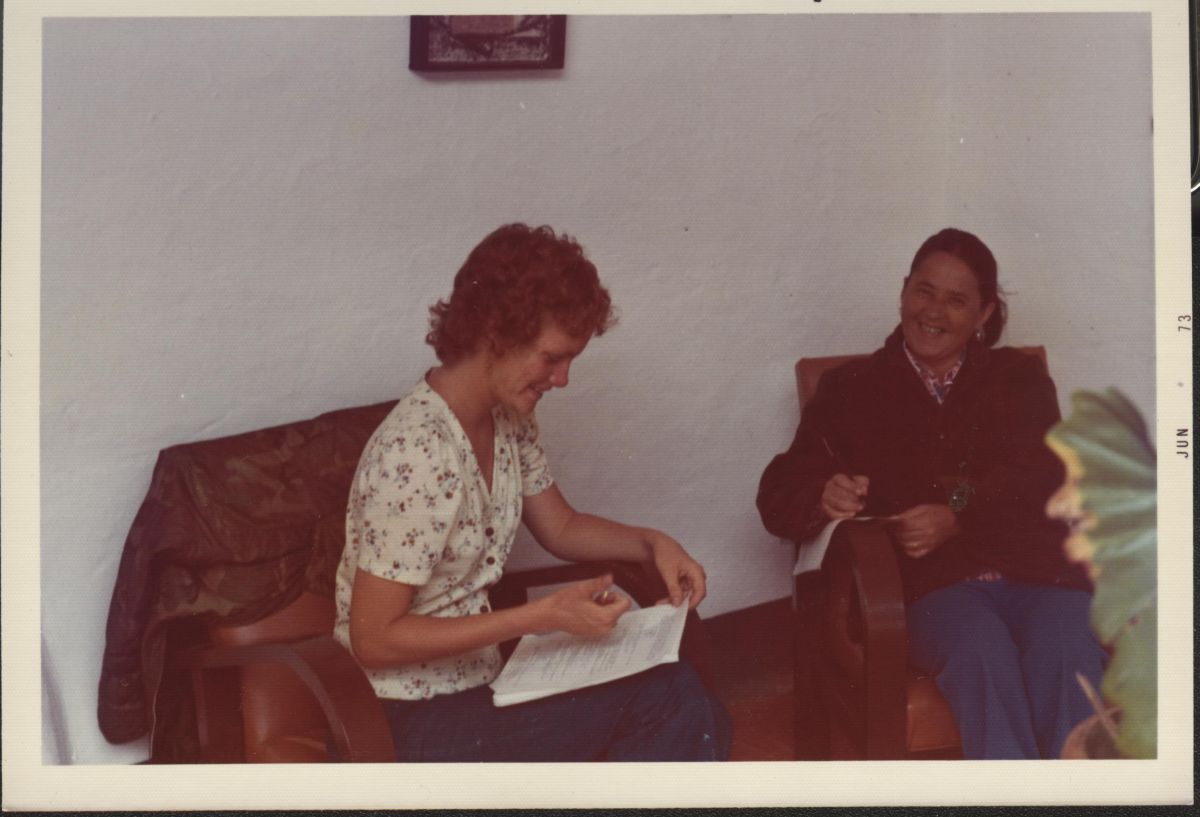

For her research project, Smith used a questionnaire to measure the differences between how participants thought about a country’s government versus the people of that country. She went around, picked a house on a block to interview, and did one round of interviews with people concerning the typical Colombian, the typical American, the typical Russian (because Russia was the U.S.’s big rival back then), and the typical Brazilian. She asked general questions, like “What do you think about them?” Two weeks later, Smith did another round of interviews and asked their opinions concerning the typical government of those same places.

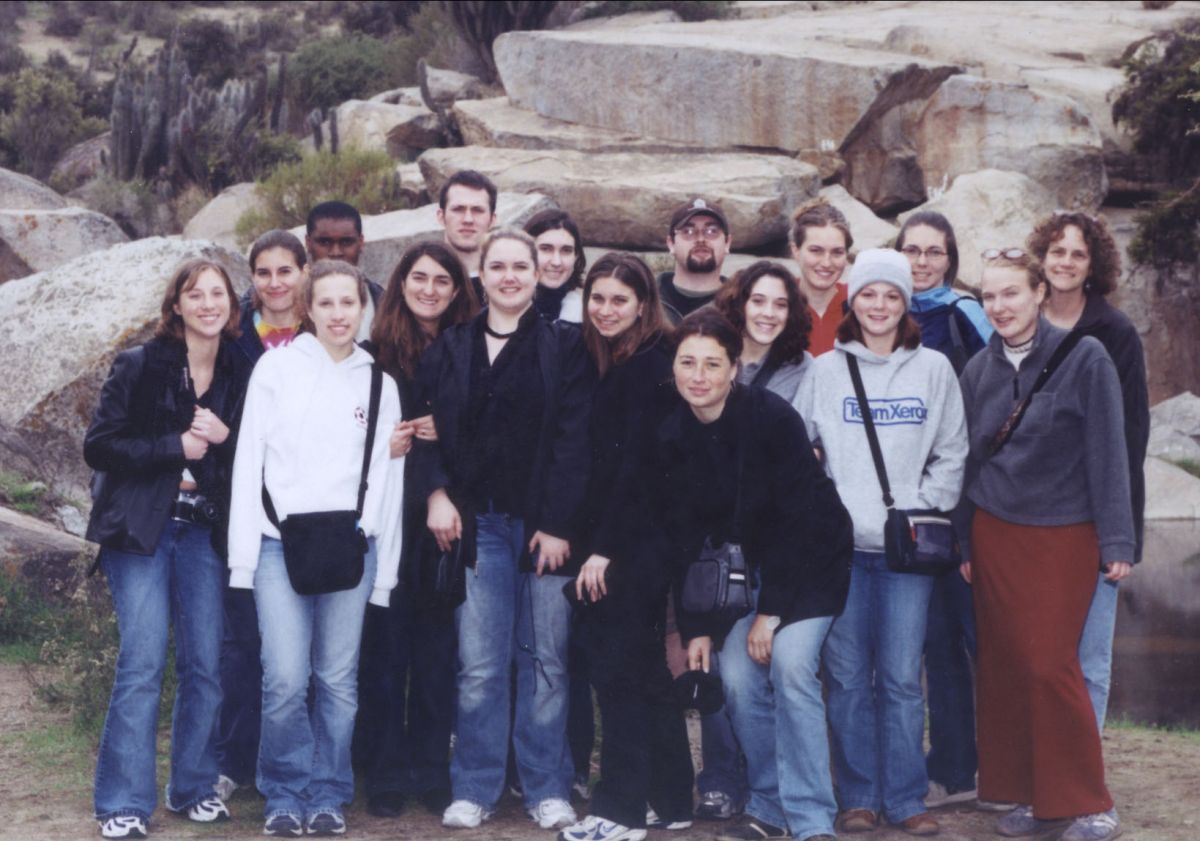

Thirty years later, Smith (now the Associate Director of Pitt’s English Language Institute) led a Seminar/Field Trip group to Valparaíso, Chile, and helped the group gain a new perspective of the world and create fixed bonds with a place and its people just has she had in Colombia twenty years earlier. “Sending people from any country to any other country is a good thing, especially when they can get into culture a little bit deeper than just that superficial touring and looking around and seeing what you see; rather living with a family, and meeting neighbors and seeing interactions that you don’t see from the outside, make this program more meaningful.”

led a Seminar/Field Trip group to Valparaíso, Chile, and helped the group gain a new perspective of the world and create fixed bonds with a place and its people just has she had in Colombia twenty years earlier. “Sending people from any country to any other country is a good thing, especially when they can get into culture a little bit deeper than just that superficial touring and looking around and seeing what you see; rather living with a family, and meeting neighbors and seeing interactions that you don’t see from the outside, make this program more meaningful.”

Although Smith had been involved in the program as both an undergraduate student and an instructor, she did not know how the program came to be. As a student and instructor, she was told, “some scholarship money was available,” but not that the money was a gift from one couple for the entirety of the program’s existence. “It didn’t occur to me to come from an anonymous donor, I thought that it was institutional money like from some grant that somebody had,” Smith explained. “And it was only really with the 50th anniversary that I really focused on it.”

The donors were not able to attend the 50th anniversary celebration of CLAS, but it was then that their support was made public. And while the donors had not been able to talk with the students face-to-face, word gets around to them about the achievements and milestones of many of the students involved. That desire to communicate goes both ways, says Smith. “I want to meet them and shake their hands and say thank you for all that they have given because I think they have just done 40 years of service to Latin America, to the University…it’s been 40 years of groups going to Latin America and of young Americans creating a connection with people in countries that have big issues with American government policy. When we establish a personal connection on that individual level, it transcends what we think about whatever issues exist between governments.”

If anyone understands what this program means to the donors and participants, it is Shirley Kregar. The former Associate Director of Academic Affairs and CLAS staff member for 40 years, Kregar has watched as hundreds of students traveled to Latin American countries with the program. “From the beginning we had many students who were very vocal about what this program did for them as far as, not only a career, but personal abilities,” said Kregar. “Before participating in the program, most students, or very few, were capable of going into the field, doing a field research project, going out, interviewing people who they’ve never met in a language that some are very good with and some are struggling. They’re good in the classroom, but to take it to the field is a whole different story.”

As a former member of the Peace Corps in Peru, Kregar knows a thing or two about the difficulties of working or studying abroad, especially when a language or cultural barrier exists. “You can’t translate the United States to another country,” she said. But with struggle comes more reward: a better understanding of one’s self and an appreciation of other cultures.

Kregar has remained in contact with many of the participants, some since the 1970s, and many of them have also remained in touch with their host families. “At the 50th anniversary celebration, I was absolutely delighted that there were people there from field trips that took place in the 70s and 80s,” remembered Kregar. “These people are now professors, deans, they’ve just gone everywhere, they are in the state department, and they are advocating what this program is for: an exchange of ideas and a conversation, a two-way conversation.”

Ever since the program was born in 1972, Kregar has remained close with the anonymous donor couple, and they with her. “They feel as I do that these students have a very strong connection to them because of the program and I feel the same,” said Kregar. “The program wouldn’t be possible without them.”

What made this couple so uncommonly special was just what it was they were giving: the couple gave the Center a large portion of their modest income so that students of Latin America and Latin Americans themselves would benefit, and as Kregar points out, “That’s even more meaningful than if you have this multimillion-dollar corporation or even multimillion-dollar couple giving donations to make the program possible.”

But for the past 40 years, participants in the program were not able to thank the people who gave them this opportunity because they didn’t know they existed. Why? “They are humble people and they don’t want the glory, the acclamation; that’s unusual in this world right now, I think.”

In the 1960s, Bob and Ursula—the future anonymous benefactors of over 500 Pitt students—met at a Spanish-language school in Cuernavaca, Mexico. Bob, a Catholic priest, and Ursula, a Catholic sister, were both twenty-somethings who wanted to work in Latin America, but first needed a firm grasp of the language. Unfortunately, that did not come easily for Bob. “Yeah, I had trouble with my language learning,” chortled Bob, “and besides that, I was convinced by a man who at that time was quite famous, Ivan Illich—he was kind of a revolutionary guy—who was doing some teacher training at the language school. And he was very much opposed for Americans, United States padres going to Latin America. Of…what’s the word, Ursy?”

Ursula responded, “Exporting United States culture into Latin America.”

“Yes,” he said. “So I decided I wouldn’t go to Panama and I went back to my place where I was a priest in Fort Wayne, Indiana.”

Ursula, a trained nurse, was determined to go on to Venezuela where she lived with a Venezuelan family. As a medical mission sister with recently acquired Spanish-speaking skills, Ursula was sent to the University of Zulia in Maracaibo, a city in northwestern Venezuela. Nursing courses never had been taught there before, so Ursula had to create them herself.

Her first task was teaching maternity nursing. “I could do the book part,” she explained, “but I had very little experience in maternity nursing. I had a friend in the community who was a midwife who helped me and was there for the deliveries.”

The hospital was a large state-run institution with an inadequate number of staff. “It was just crazy that it was so understaffed that one day I was finishing up with the students at lunchtime and I heard a woman grunting in the corner–the delivery rooms were 6-8 women to a room–and so I ran over to the corner and I caught her baby as it was born,” Ursula said with a chuckle. “It would have landed on the floor otherwise.”

At only 25 years old, she taught the first class to graduate from a baccalaureate program in nursing at a Venezuelan university.

While Ursula taught in Maracaibo and Bob worked in Fort Wayne, they kept in touch through letters. After Ursula returned to the States, Bob wrote to her saying that he was leaving the priesthood. “He wrote, would I think about spending my life with him? And I called him up and said, “Yes,” and woke everybody up in my house.” They both giggled.

Bob got a job at a mental hospital in the Pittsburgh area, and Ursula said she would go with him to Pittsburgh and work with its Latin American community. “Well there wasn’t one!” exclaimed Ursula as Bob chuckled in the background. Instead, they found Pitt’s Center for Latin American Studies and its first director, Cole Blaiser.

“We just said that we were interested in education and that we could maybe contribute to a program there and he introduced us to the idea of starting the summer research program,” said Bob.

This summer (2015), 14 undergraduate students will travel to San José, Costa Rica through the Seminar/Field Trip program.

“We’re blessed that we can do things like this,” said Bob. “It is just a little bit of us that we have invested in the development of countries in Latin America.”

Ursula couldn’t agree more. “I just think it is terribly important for Americans to know how other people live, and what the culture is like, especially since they’re our neighbors.”

“It’s just amazing,” exclaimed Bob, “for the little bit that we have contributed really to this kind of program, we just feel so joyful that so little has done so much in influencing of the students to do the kind of work that we so much believe in.”

Why Latin America specifically?

“I just love the people,” said Ursula. “Oh gosh, they were just so friendly and warm and…well, didn’t you find that?”