Join us for Book Readings:

Join us for Book Readings:

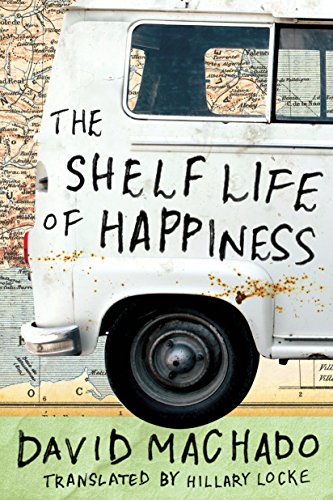

The Shelf Life of Happiness by David Machado

Ripped apart by Portugal’s financial crisis, Daniel’s family is struggling to adjust to circumstances beyond their control. His wife and children move out to live with family hours away, but Daniel believes against all odds that he will find a job and everything will return to normal.

Even as he loses his home, suffers severe damage to his car, and finds himself living in his old, abandoned office building, Daniel fights the realization that things have changed. He’s unable to see what remains among the rubble—friendship, his family’s love, and people’s deep desire to connect. If Daniel can let go of the past and find his true self, he just might save not only himself but also everyone that really matters to him.

About the Author

David Machado hails from Lisbon, Portugal, and writes fiction for both adults and children. His books are popular in Portugal and have been awarded literary prizes, including the European Union Prize for Literature for the Portuguese version of this novel, Índice médio de felicidade (The Shelf Life of Happiness), which he adapted into a screenplay in 2016. When he's not traveling, he lives in Lisbon with his wife and two children.

About the EUPL

The European Commission, which acts as the executive branch of the EU, funds the EU Prize for Literature through the Commission’s Creative Europe program, which aims to recognize European art and talent and promote international discussion. The prize is awarded to each of the twelve nations participating in the contest that year. Of the thirty-six total member states in the program, twelve nations are eligible each year for judging, allowing all states and languages to be recognized throughout a cycle of three years. The prize requires winning books to come from established authors, not be translated into more than three languages, and to be the author’s most recent work. Winning books are selected by National Juries chosen by several intra-Europe publishing and editing councils. Find more information here.

Explore the EUPL

Please take note of the anthologies dating back to 2009 on this page.

Some ideas to ponder as you investigate:

-

On page 10, Xavier asks why people don't ask for help when they need it, a phenomenon which is repeated throughout the novel (and is embodied by Daniel). Why don't people ask for help when they need it? Is asking for help a subtractive process? If so, what does one stand to lose?

-

Xavier seems to struggle with mental illness, as do other characters in the novel (to varying degrees), yet he is treated in a cavalier fashion by others. Is there any evidence to suggest that this approach is representative of the Portuguese treatment of the mentally ill, and how does this compare with that of the U.S.?

-

The more Daniel tries to quantify his happiness, the more his value vacillates and seems to worsen—are we wrong in trying to quantify our happiness?

-

Xavier won't implement his plan of moving to increase his happiness because it would first need to decrease. Is this realistic? Do we have to be unhappy before we can be happy?

-

Daniel keeps an obsessive blueprint of his life called, "The Plan." In what ways does this document affect his happiness? In what ways does structure increase our happiness? In what ways does it hurt it?

-

In what ways does Daniel use Almodovar's imprisonment to justify his own separation from his family? Consider Almodovar's imprisonment, Daniel's self-exile, and Xavier's reclusiveness—how are they similar? How are they different?

-

Daniel wonders why a video of violence attracts more views than a website for people who need help. How would you explain this phenomenon?

-

Both Doroteia and Daniel are driven by hope, but their levels of happiness are drastically different, as are their responses to help from others. How does hope impact our happiness?

Questions by EURO-TAM Excel @ Carolina Student, Brett Harris

Funding provided by the International and Foreign Language Education (IFLE) office of the U.S. Department of Education and through a Getting to Know Europe Grant provided by the EU Delegation to the U.S..